COMMENTARY

Hope for Sea Turtles, One Hatchling at a Time

By WAYNE CREED

June 30, 2014

A few years ago, when my work was based near Oceana Naval Air Station, one of my guilty pleasures was to sneak over to the Virginia Aquarium during lunch and hang out by the loggerhead turtle exhibit. Light and graceful swimmers, those blithe movements belie the power and strength held in their huge heads and jaws which are easily able to crush right through a conk shell. Another guilty pleasure is being able to treat my wife to some sort of pampering from the wonderful Breezes Day Spa in Cape Charles. Recently, these two guilty pleasures sort of came together to help shed light on a scientific mystery that had been plaguing marine biologists for some time.

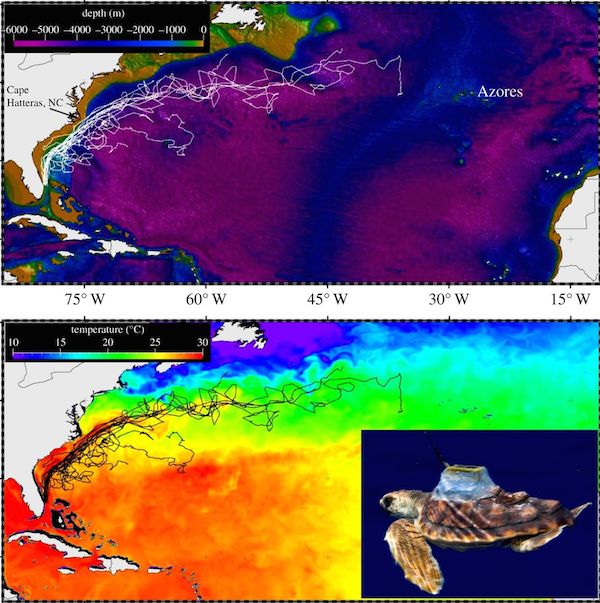

After Loggerhead sea turtles hatch, they begin a frantic race off the beach into the surf. Once into the sea, the hatchlings start a journey that lasts several years, and when it’s finished, leaves them across the Atlantic near the Canary Islands. How they get there, however, has always remained a mystery. The time between hatching and rediscovery has always been referred to as the turtle’s “lost years.”

For some time now, marine scientists at NOAA have been using satellite tracking devices to monitor the travels of adult turtles. The transmitters are glued to the shell, and location data is beamed back and captured. This worked fine for adults, but young turtles grow so quickly that their shells shed whatever scientists tried to use to attach the transmitters. It was here that a professional spa technician, like those working at Breezes, provided a breakthrough.

Marisol Marrero, who is a nail salon technician at Not Just Nails in Boynton Beach, Florida, had a customer, Jeanette Wyneken of Florida Atlantic University, who was also part of NOAA’s Southeast Fisheries Science Center study tracking loggerheads. While getting her nails done, Wyneken was reflecting on the problem of getting the transmitters to stick to the baby turtles’ shells, which she mentioned are made out of a protein called keratin, the same material as fingernails. Ms. Marrero suggested that they try a similar technique that the salons used for attaching artificial nails: try using an acrylic base coat. Wyneken took the suggestion back to the lab and tried it. It worked. This serendipitous trip to the salon has helped to finally shed new light on sea turtles’ “lost years.”

CONTINUED FROM FIRST PAGE

It had been assumed that loggerheads would enter the North Atlantic Gyre (a circular system of currents that flows clockwise from North America to Europe and Africa) and then passively hang on until reaching the Canary Islands. Being able to finally track their migration, the transmitters show that many turtles swim off the gyre into the Sargasso Sea. The effort to do so makes sense, as, once in the midst of the sargassum seaweed, the young turtles not only find refuge from predators, but also, being cold blooded, the warm waters allow them to grow faster (and outgrow those same predators).

Illuminating the turtles’ lost years is certainly a good thing, yet it doesn’t do much to assuage the many factors that are leading to population declines. Immediate dangers, such as gill nets, pelagic long lines, dredges, and trap pot fishing gear cause serious injuries, while trawlers not outfitted with Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDS) can cause trapped turtles to die through drowning.

Juvenile loggerheads spend a good deal of time in the open ocean (pelagic) where increasing amounts of marine debris such as plastic bags mix with parts of their normal diet (plastic bags look a lot like jellyfish). Ingesting this debris has led to increased mortality rates for loggerheads.

In Pat Conroy’s novel, Beach Music, his character Lucy McCall highlights one of the biggest threats to loggerheads. Dying of leukemia, she makes it her last calling to maintain and even increase the loggerhead nesting areas around the beaches of Beaufort, South Carolina. Increased development along coastal areas, while seeking to stave off natural erosion via beach sand nourishment and breakwaters, has led to a severe loss of nesting areas. While these techniques may produce more sand, it is usually not beach quality, especially for nesting females. Like anything, sub-optimal nesting habitats produce weaker nest construction, and reduce the chances that eggs and hatchlings will survive. These same beach armoring techniques, such as revetments, sandbags, and bulkheads also impede loggerhead access to the dunes (usually the optimal nesting areas).

Lucy’s McCall’s desire to shoot out all the lights along the beach with a shotgun (an enjoyable and relatable notion) may have seemed extreme, yet artificial lighting on or near the beach may deter adult female turtles from emerging from the ocean to nest and can disorient emerging hatchlings away from the ocean (hatchlings base their orientation toward the brightest direction, which is normally toward the open horizon of the sea). Hatchlings don’t have much time to get to the sea, so being lured towards sidewalks and parking lots produces a much higher than normal mortality rate.

Despite a continued downward trend for loggerheads, there are groups that are working hard to reverse the numbers and get these turtles back on track. The National Marine Fisheries Service has been leading pragmatic efforts to work with conservation groups such as Ocean Trust, Pew, World Wildlife Fund, and Oceana to help foster partnerships with the fishing industry. These partnerships attempt to apply more turtle-friendly techniques such as the use of TEDS, non-offset circle hooks, and turtle-exclusion pound and gill netting. Winning devices have been designed to minimize the bycatch of turtles on tuna long lines and help turtles avoid gillnets altogether. Also, using whole finfish for bait and avoiding pelagic long line fishing in waters 68 degrees or above can help avoid turtle interactions.

On the geographic front, more work needs to be done to establish marine protected areas to ensure sea turtles have a safe place to nest; more funding for the monitoring and patrolling of turtle nests, as well as equipping local turtle conservationists is also needed. Donating to these organizations is always best, but also finding ecotourism opportunities that lead to turtle conservation efforts is another way for ordinary folks to get involved. These tourism dollars many times lead to alternative livelihoods in turtle conservation.

I never need to be enticed into having a martini, but Bonefish Grill has turned another guilty pleasure of mine into a way to help. In support of Ocean Trust, Bonefish Grill has introduced the Ocean Trust Tropic Heat Martini. Each martini will generate $1 for Ocean Trust. The Bonefish Martini project may seem frivolous, but it highlights a successful strategy of partnership that is leading to dramatic success stories, not just for loggerheads, but for green, leatherback, and the mysterious Kemp’s Ridley. For almost 30 years, Ocean Trust has been working on the beaches of Mexico to help protect nesting Kemp’s Ridley females. With this year’s funding in danger, Ocean Trust’s strategic partners in the fishing industry, the Texas and Southern Shrimp associations, stepped in to fill the funding gap, allowing for over a million hatchlings to be released in the Gulf of Mexico. It is this kind of strategic, pragmatic, partnership approach between conservation and the fishing industry that provides some hope for sea turtles, one hatchling at a time.

Submissions to COMMENTARY are welcome on any subject relevant to Cape Charles.

Comments